He kissed his weeping wife and children goodbye, telling them what they knew too well—that he might never return. Then the West Pakistani soldiers prodded him down the stairs, hitting him from behind with their rifle butts. He reached their jeep and then, in a reflex of habit and defiance, said: “I have forgotten my pipe and tobacco. I must have my pipe and tobacco!”

This is how Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, popular as Bangabandhu among his followers, was narrating his story of getting arrested in the early hours of March 26, 1971, within a few hours of the launching of the Pakistan Army’s brutal massacre in Bangladesh. The report was published in The New York Times on January 18, 1972, shortly after his release from Pakistan’s jail and return to Bangladesh.

How he was arrested

According to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, he was arrested in the early hours on March 26, 1971 from his home by a small team of Pakistan Army who stormed into his house. Here’s what he said to Sydney H. Schanberg of The New York Times.

—

The West Pakistani attack throughout the city began at about 11 P.M. and quickly mounted in intensity. The troops began firing into Sheikh Mujib’s house between midnight and 1 A.M. He pushed his wife and the two children into his dressing room upstairs, and they all got clown on the floor as the bullets whizzed overhead.

The troops soon broke into the house, killing a watchman who had refused to leave, and stormed up the stairs. Sheikh Mujib said he opened the door of the dressing room and faced them, saying: “Stop shooting! Stop shooting! Why are you shooting? If you want to shoot me, then shoot me; here I am, but why are you shooting my people and my children?”

After another flurry, a major halted the men and told them there would be no more shooting. He told Sheikh Mujib he was being arrested and, at his request, allowed him a few moments to say his farewells.

He kissed each member of the family and, he recalled, said to them: “They may kill me. I may never see you again. But my people will be free someday, and my soul will see it and be happy.”

He was driven to the National Assembly building, “where I was given a chair.”

“Then they offered me tea,” he recalled in a voice that became mocking. “I said, ‘That’s wonderful. Wonderful situation. This ‘is the best time of my life to have tea.’”

After a while, he was taken to “a dark and dirty room” at a school in the military cantonment. For six days, he spent his days in that room and his nights—midnight to 6 A.M.— in a room in the residence of the martial law administrator, Lieut. Gen. Tikka Khan, the man the Bengalis consider most responsible for the military repression in which hundreds of thousands of Bengalis were tortured and killed.

On April 1, Sheikh Mujib said, he was flown to Rawalpindi, in West Pakistan—separated from East Pakistan by over a thousand miles of Indian territory—and then moved to Mianwali Prison and put in the condemned cell. He passed the next nine months alternating between that prison and two others, at Lyallpur and at Sahiwal, all in the northern part of Punjab Province. The military Government began proceedings against him on 12 charges, six of which carried the death penalty. One was “waging war against Pakistan.”

Call for Resistance

In this interview, Sheikh Mujib claimed he sent what he termed a “last message to people” in a clandestine headquarters in Chittagong, which was “recorded and later broadcast,” and he called to resist the army attacks.

—

By 10 P.M., Sheikh Mujib had received word that West Pakistani troops had taken up positions to attack the civilian population. A few minutes later, troops surrounded his house, and a mortar shell exploded nearby.

He had made some secret preparations for such an attack. At 10:30 P.M., he called a clandestine headquarters in Chittagong, the southeastern port city, and dictated a last message to his people, which was recorded and later broadcast by a secret transmitter.

The gist of the broadcast was that they should resist any army attack and fight on, regardless of what might happen to their leader. He also spoke of independence for the 75 million people of East Pakistan.

Sheik Mujib related that after sending his message, he ordered away the men of the East Pakistan Rifles, a paramilitary unit, and of the Awami League, his political party, who were guarding him.

A Contested Claim

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s claim of sending a ‘last message’ contradicts other narratives propagated by his party, the Awami League, decades later.

Every communication is supposed to have two key elements—the sender and the receiver—and if the message is sent from the sender’s end but is not received by the receiver’s end accordingly, the communication is not completed. So, who received Sheikh Mujib’s ‘last message’?

BDR (EPR) Wireless Story

In a public address at Bangladesh Rifles Headquarters on December 5, 1974, Mujib claimed that he sent a message to Chittagong’s BDR (then EPR) Headquarters saying, “From today, Bangladesh is independent.” A local media outlet reported this 49 years later.

Awami League, Mujib’s own party, made a slightly different claim regarding this, however. According to an archived article published and widely publicised titled Bangabandhu and the Declaration of Independence, Sheikh Mujib sent two messages that night, and this was the ‘second message’.

The second message reads: “Message to the people of Bangladesh and the people of the world. Rajarbagh Police Camp and Peelkhana EPR suddenly attacked by Pak Army at 2400 hours. Thousands of people killed. Fierce fighting going on. Appeal to the world for help in the struggle for freedom. Resist by all means. May Allah be with you. Joy Bangla.” The message was transmitted by the EPR wirelesses throughout the country at around 1.30 am.

The problem with this narrative is that the commander of Chittagong’s EPR unit, Rafiqul Islam Bir Uttam, who later became a leader of Mujib’s party, the Awami League, did not mention any incident of receiving a message from Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in his memoir A Tale of Millions, nor anything about recording or broadcasting it.

The relevant chapter of the book is embedded here for the readers.

Hence, it is unclear whether Mujib’s message was ever properly received by EPR, which later became BDR, and if it was received, by whom and why it has not been reported.

Curious case of David Loshak

Awami League’s website claims there was a ‘pre-recorded’ first message that was circulated targeting foreign journalists and diplomats. The article reads:

The message was on the air from a handy little transmitter purposely set up in the Baldha Garden targeting at the foreign journalists and diplomats who were the listeners to Radio Pakistan Dacca. The London Daily Telegraph correspondent David Loshak, then in Dhaka on duty, was one who listened to the declaration and upon return to London wrote a book called Pakistan Crisis, which refers to the harrowing incidents of Yahya Khan’s unprovoked repression of the innocent East Pakistani people and Bangabandhu’s declaration of Bangladesh’s independence urging people to put up a strong resistance.

There are multiple issues with this narrative.

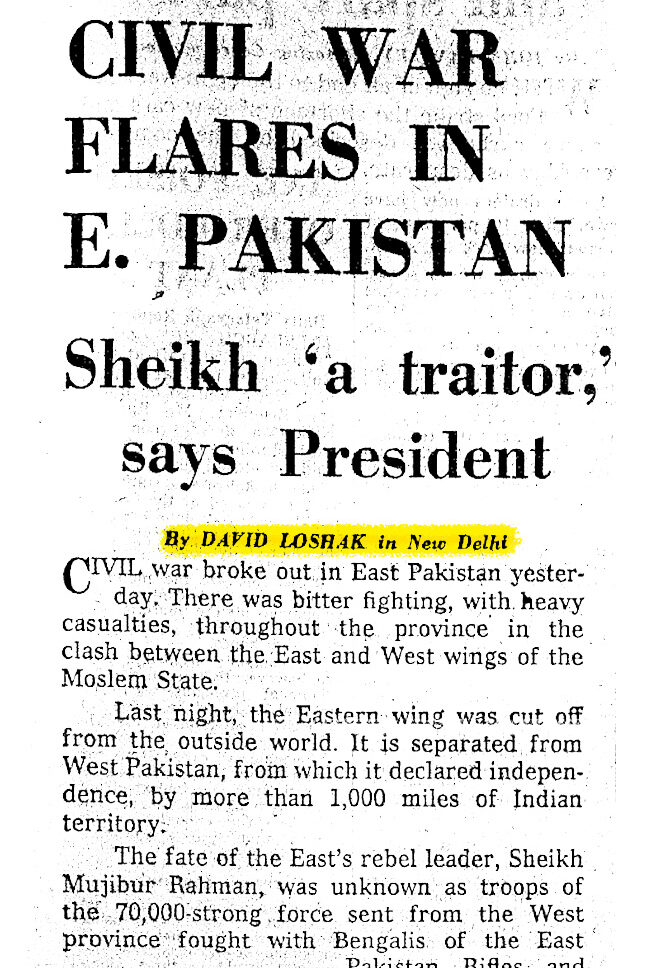

First, The Telegraph’s correspondent, who was in Dhaka at that time, was not David Loshak; it was Simon Dring. David Loshak was in New Delhi at that time. He published a report on March 27, 1971, ‘Civil War Flares in E. Pakistan’; the byline of the report was David Loshak in New Delhi.

Loshak’s report mentioned, “Troops loyal to Sheikh Mujib claimed to have captured the Chittagong station of Radio Pakistan, forcing the Government troops to retreat after fierce fighting. Last night, on a clandestine radio calling itself “The Voice of Bangla Desh” (Free Bengal), the Sheikh proclaimed the province “the Sovereign Independent People’s Republic of Bangla Desh.”

However, Loshak also mentioned in his report that some parts of the report were ‘unconfirmed’ and filtered ‘through the border with India’.

Loshak wrote a book on the crisis in Pakistan and the emergence of Bangladesh, published in 1971 in London, titled ‘Pakistan Crisis. On page 89, he wrote:

They [the resistance of defecting Bengali army, EPR and youth] were sustained, for a time, by the broadcasts of the clandestine ‘Radio Bangla Desh’. Soon after darkness fell on March 25, the voice of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman came faintly through on a wavelength close to the official Pakistan Radio. In what must have been, and sounded like, a pre-recorded message, the Sheikh proclaimed East Pakistan to be the People’s Republic of Bangla Desh. He called on Bengalis to go underground, to reorganize and to attack the ‘invaders’ […] Radio Bangladesh continued to broadcast, but its claim grew wilder and lost credibility. In soon became obvious that it was not even located in Bangla Desh, but in India.

This is an interesting narration of the story at a time when Bangladesh was not even recognised as an independent country. The book includes a Chronology of events that ends on April 17, 1971, with the formation of the provincial government, and the preface reads:

[I]t is not an academic book. This certainly does not mean that I played fancy-free with facts, but it does mean that I have left many details of ephemeral significance to the PhD theses, in the interest of the general reader.

This means that the writer has acknowledged that the book is written for the general reader and lacks crucial details. Hence, any informed reader should not draw conclusions about events with great significance based on the book’s narration.

However, from David Loshak’s reporting and the book’s narration, it is clear that he did not ‘listen to the declaration’ himself and relied on his sources, some of which were unconfirmed. Note that he was reporting from New Delhi at that time, and Bangladesh was cut off from the rest of the world, making it nearly impossible for a journalist based in Delhi to report accurate events.

But one person from his newspaper was there, in Bangladesh, to report the details, Simon Dring, the correspondent of The Telegraph, who flew to Dhaka on March 6, 1971, and according to a 30th March report, ‘slipped the net’.

As the Pakistan Army rounded up journalists in the Intercontinental Hotel, from where they were reporting back to their respective outlets, Simon Dring managed to evade their eyes, hiding on the rooftop of the hotel. He left Bangladesh for Bangkok after making the rounds in and around Dhaka.

Simon Dring published his report on March 30, 1971, from Bangkok. The report, titled ‘Tanks Crush Revolt in Pakistan,’ includes a detailed description of the events surrounding the March crackdown but does not mention anything as such.

A copy of the report is attached below for the interested readers.