History of Bangladesh in a nutshell

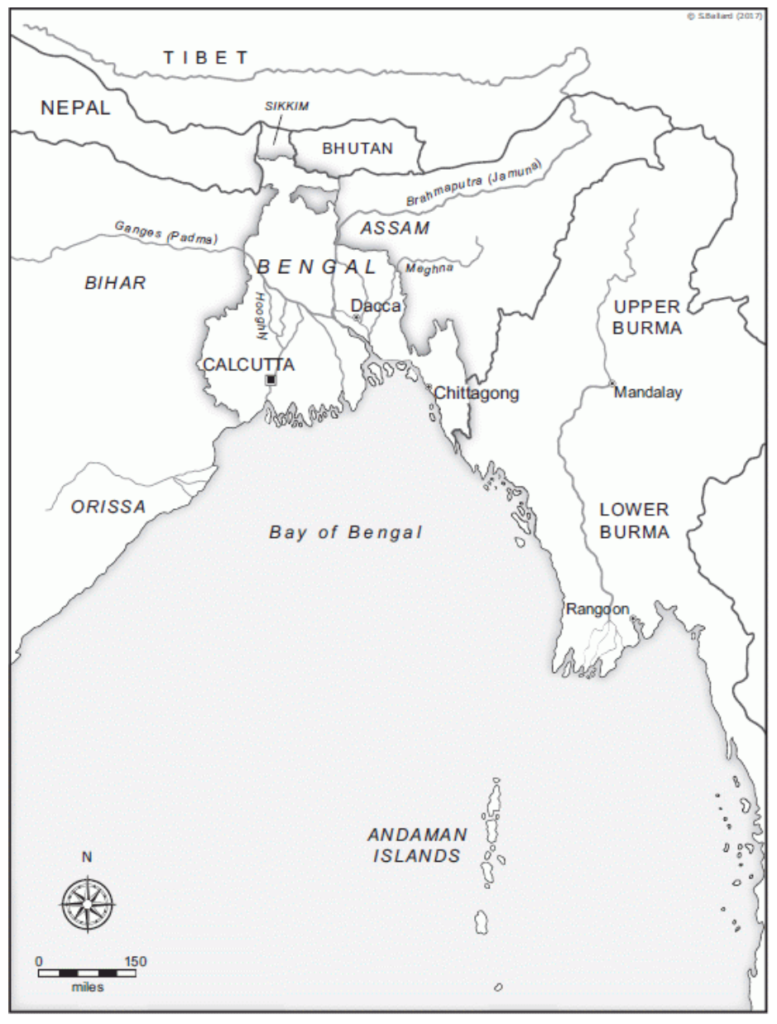

Bengal, one of the most affluent provinces of Mughal India, later became virtually independent and was ruled by Nawabs. In 1757, the British East India Company annexed Bengal after defeating Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah in the Battle of Plassey.

Exactly a hundred years later, Bengal became part of British India, like other provinces annexed by the British East India Company, ruled by the monarchy of the United Kingdom.

A series of catastrophic incidents, both manmade and natural, marked the subsequent two centuries of rule, including the 1943 Bengal Famine that claimed millions of lives.

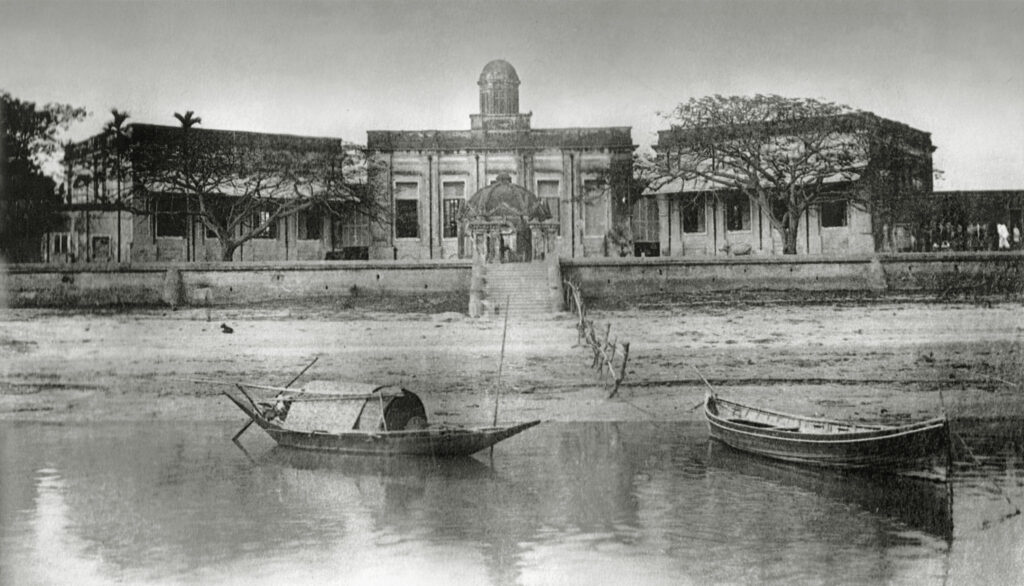

However, supporters of British colonial rule often take pride in introducing some modern technologies to the Indian populace and investing in the communication and medical sectors.

British rule ended in 1947 when they divided British India into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan. Bengal was also partitioned, and Hindu-majority West Bengal became part of India, while Muslim-majority East Bengal became East Pakistan.

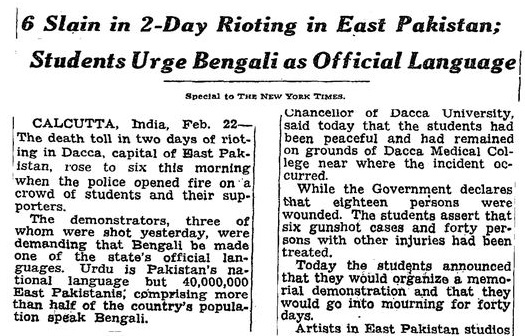

The first major upheaval in East Pakistan was centred around the decision to impose Urdu as the state language of Pakistan, initially by Muhammad Ali Jinnah and, after his death, by Muslim League politicians. In February 1952, the movement peaked, and from February 21 onwards, dozens died in East Pakistan while protesting the decision.

This movement ignited the flame of Bengali nationalism among Pakistan’s Bangla-speaking populace. The immediate effect was the formation of the United Front, which was comprised mainly of Bengali leader-led parties. It won a landslide victory in the 1954 election. However, in 1958, martial law was imposed, and military general Ayub Khan eventually took over as the President of Pakistan.

Ayub Khan pushed for a new form of democracy, Basic Democracy, and publicised the narrative of the ‘Development over Democracy’ in search of performance legitimacy. Ayub accused Mujib of trying to gain East Pakistan’s independence from Pakistan with India’s support after Sheikh Mujibur Rahman presented a six-point demand for greater autonomy for East Pakistan. As a result, a case known as the Agartala Conspiracy case was filed against Mujib, along with other politicians and Bengali military officials.

Ayub’s rule ended in 1969 when people and students from both parts of Pakistan occupied the streets, demanding Ayub’s resignation. In East Pakistan, the ‘Prophet of Violence’ Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani played a crucial role.

After Ayub’s fall, the army chief Yahya Khan took charge and declared to hold an election within a year. Yahya’s plan was severely disrupted when the deadliest cyclone in recorded history hit East Pakistan and claimed hundreds and thousands of lives. The dysfunctional warning systems, lack of coordination in relief efforts and the general apathy towards the Bengalis among West Pakistan’s military junta made the call for greater autonomy for East Pakistan more popular.

Riding on the sentiment and flame of Bengali nationalism, the AL, led by Sheikh Mujib, swept through both the national and provincial assemblies in East Pakistan. The party shared a draft constitution for Pakistan based on its six-point demand, ensuring that no law would contradict Islam.

However, Yahya Khan and the military junta, along with West Pakistan-based minority leader Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, refused to allow Mujib and AL to rule Pakistan, ordering a genocide in March 1971.

The war for liberation broke out in the early hours of March 26. Sheikh Mujib was arrested from his home and was flown to West Pakistan.

A declaration of independence, attributed to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, was initially circulated on March 26. Mujib later claimed that he sent a message to the Chittagong unit of EPR before his arrest. However, the commander of the unit, Major Rafiqul Islam, did not mention receiving anything as such in his memoir.

A fresh declaration came from Chittagong radio on March 27, proclaimed by Major Ziaur Rahman of the 8th East Bengal Regiment, who revolted against the Pakistan military and took control of the city. Bengali soldiers from other parts of the country also revolted and joined the liberal struggle.

In the first week of April, the military officials who revolted against Pakistani rule met at a tea garden in Sylhet’s Teliapara to discuss engagement strategies. The four commanders, Ziaur Rahman, Khaled Mosharraf, KM Shafiullah, and MA Rab, initially divided Bangladesh into four sectors.

Later, on 17 April 1971, a provincial government was formed, with Tajuddin Ahmed as the prime minister. The country was divided into eleven sectors. The government appointed sector commanders for each sector, who led the war efforts in their respective sectors.

From August to September, three brigades were also formed, led by Ziaur Rahman (Z Force), KM Shafiullah (S Force), and Khaled Mosharraf (K Force). They led full-fledged attacks from the Eastern Front.

Freedom fighters gradually liberated each part of the country, and the war gained momentum in late November. By early December, most parts of Bangladesh were liberated.

Meanwhile, the Pakistani Army, supported by local collaborators, most notably Ghulam Azam, Nurul Amin, AKM Yusuf and Tridiv Roy, was committing genocide, killing hundreds of thousands in each part.

After a 9-month-long liberation war and at the cost of an estimated 3 million lives, Bangladesh was liberated on 16 December 1971.

On January 10, 1972, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman returned from Pakistan’s jail and assumed his role as President. A constituent assembly was formed with the pro-liberation members who had won the 1970 election from the Awami League. Mujib became the Prime Minister soon.

After assuming power, the Mujib-led AL regime became increasingly authoritarian. In 1972, a paramilitary force—Jatiya Rakkhi Bahini—was established, which functioned as a private militia of Sheikh Mujib. The force, popular as Rakkhi Bahini, soon earned a reputation for brutal and deadly attacks on dissenters. In one upazila, Bajitpur of Kishoreganj, the force allegedly killed 126 opposition activists. Dozens were shot to death in the heart of the capital, Dhaka, on March 17, 1974.

The press faced severe repression, including arrests of journalists, forced resignations, and newspaper closures. Several prominent editors and publications, such as Jasad’s Gonokontho, the weekly Holiday, and Hak Kotha, were targeted for criticising the regime and subsequently shut down or faced punitive actions.

As the regime gradually became authoritarian and ruthless, corruption increased significantly. Permits and licenses for crucial goods went to people close to the Awami League, who sold and resold them, contributing to the increase in the price of essential goods.

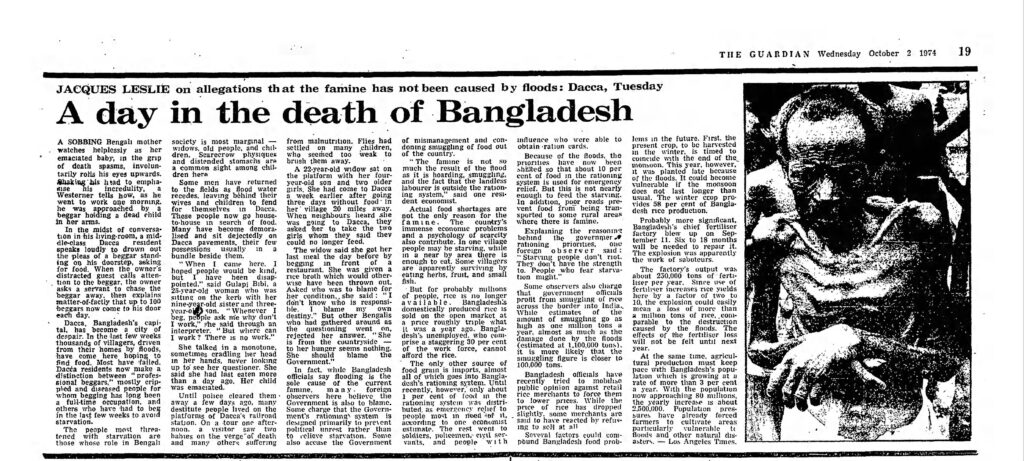

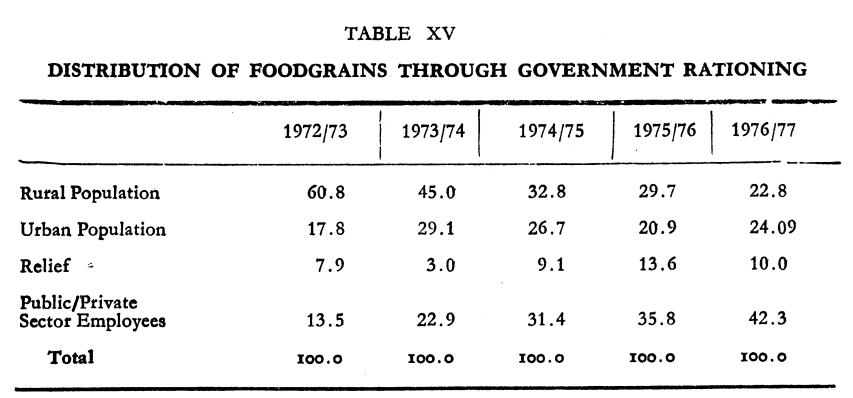

Corruption and illegal hoarding became so rampant that by early 1974, the price of rice, Bangladesh’s staple food, increased by 50%, creating a ground for famine. By mid-1974, after a deadly flood hit the country, famine went out of control, claiming around a million lives, as the government allocated only 40% of available food stock for the starving 91% of the population in the villages.

In January 1975, Mujib introduced a one-party state by amending the constitution and formed the Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BAKSAL). All but four state-controlled newspapers were banned. The political killings reached new heights.

Seven months later, in August 1975, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was brutally assassinated with most of his family members by a disgruntled group of military officials who stormed into his residence. Mujib’s long-time friend, Khandakar Moshtaque Ahmed, backed by the coup leaders, took over as the President.

In the first week of November, a coup led by Khaled Mosharraf, the army’s Chief of General Staff, toppled Moshtaque. On November 7, 1975, the loyalists of army chief Ziaur Rahman, with the support of ex-army official and Jasad leader Abu Taher, staged a counter-coup against Mosharraf. Enraged soldiers killed Mosharraf and a dozen military officials.

Ziaur Rahman emerged as the leader out of the chaos, and as Jasad planned for another coup, their leaders, including Abu Taher, were nabbed by security agencies. Taher was later sentenced to death for his role in the coup and the deaths of military officials at the hands of his supporters by a controversial military court.

Chief Justice Abu Sadat Mohammad Sayem, appointed President by Khaled Mosharraf, continued to serve as President and chief martial law administrator (CMLA). As differences between Zia and Air Chief MAG Tawab grew over the Islamisation of Bangladesh, President Sayem was pressed to hand over the responsibilities to Zia. Zia pushed Tawab off as soon as he became the CMLA and the nation’s de facto leader.

In early 1978, Sayem’s health declined, and Zia became the President. He won a controversial referendum with a large but embarrassing victory.

Ziaur Rahman shifted Bangladesh towards a capitalist system, which differed from Mujib’s socialist agenda. The ready-made garments sector was established, and manpower exports increased, contributing to the stabilisation of the economy.

However, upheavals in the military continued, and more than 20 coups occurred. To restore order, Zia went heavy-handed on the dissenters inside the army. Hundreds were executed for being involved in coups in questionable trials.

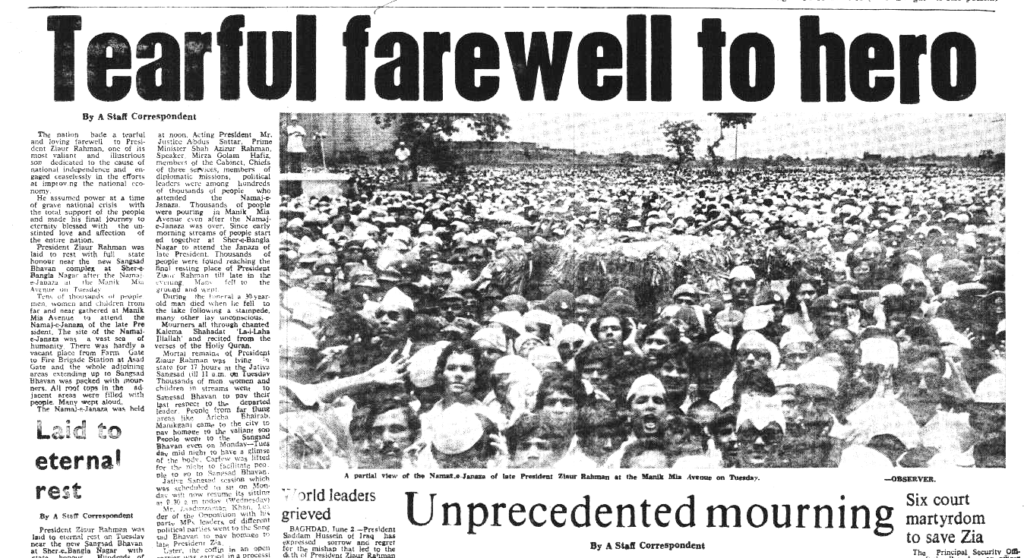

Zia died in 1981 in another abortive coup in Chittagong.

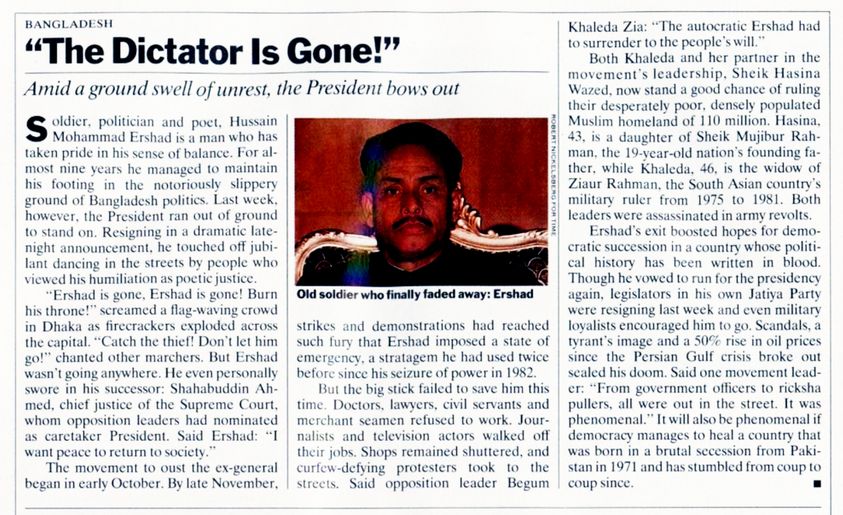

Zia’s death created a power vacuum. Though Vice-President Abdus Sattar won a landslide victory in the presidential election, he was soon deposed by the army chief Hussain Muhammad Ershad, who eventually took over the power by 1983.

Zia’s widow, Begum Khaleda Zia, and Sheikh Mujib’s daughter, Sheikh Hasina, who returned only a few days before Zia’s assassination, launched street protests to overthrow Ershad.

However, Ershad convinced Hasina and the Islamist Jamaat to participate in the 1986 national election, which Ershad won decisively. Khaleda Zia was interned multiple times before the poll as she vehemently opposed it.

Ershad’s rule was continuously challenged over the next few years, and economic woes increased. More people started to come out on the streets, and the anti-Ershad movement peaked in the late 1990s. Students formed an alliance as Naziruddin Jehad, a pro-BNP student leader, was gunned down by Ershad’s loyal cadres.

Everything stood a standstill by December as people took control of the streets, and Ershad was ousted.

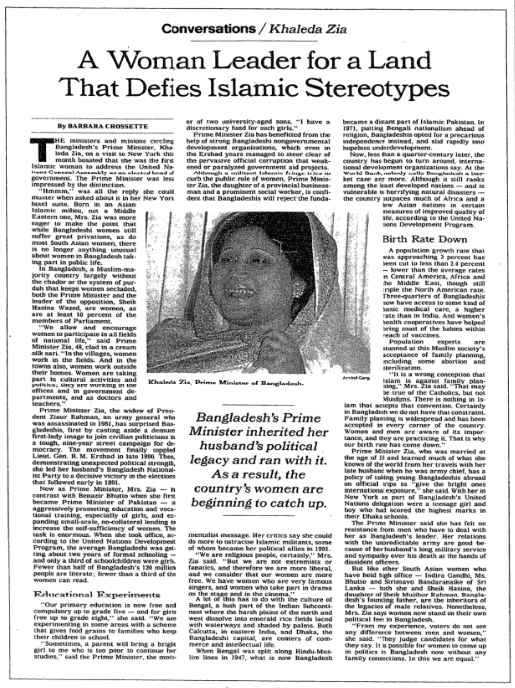

A new election was held under a nonpartisan caretaker government led by the then Chief Justice Shahbuddin Ahmed. BNP won the majority of the seats, and Khaleda Zia became Bangladesh’s first female prime minister.

Khaleda Zia introduced stipends and facilities for female students and offered free primary education. Enrolment at schools grew faster, and the gender balance situation improved. The industrial sector flourished as macroeconomic reforms were implemented, and employment in the RMG sector alone grew by 29% each year from 1991 to 1995.

Khaleda’s final days were tumultuous after her party, BNP, got involved in severe election fraud during a by-election in Magura. Parliamentarians from Hasina’s AL, Islamist Jamaat and Ershad’s Jatiya Party resigned from the parliament after issuing an ultimatum to introduce caretaker government provisions in the constitution to oversee fair elections.

A fresh but sham election was held in February 1996, in which the BNP won almost every seat. Responding to the popular demands and to subside the ongoing violence, the party introduced the caretaker government system.

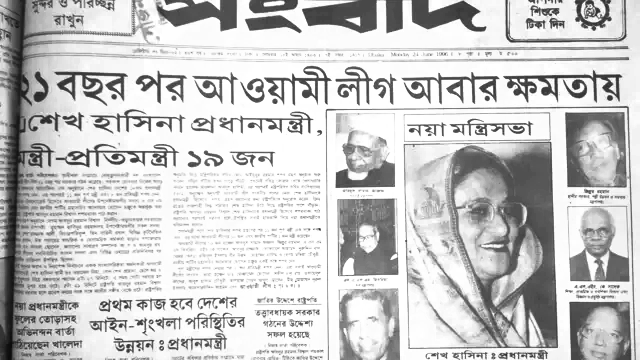

A new election was held under the caretaker government led by Justice Habibur Rahman, and Hasina’s AL won in most constituencies.

Sheikh Hasina encouraged the private sector to invest in the telecom and power sectors. With NGOs’ support, primary and secondary education grew.

The financial sector saw some irregularities, including a stock market manipulation that led to a crash and the banking sector was mired in controversies. Organised crime, which was growing during Khaleda’s tenure, peaked during Hasina’s time as local Godfathers, who were often the parliamentarians elected from her party, occupied area after area.

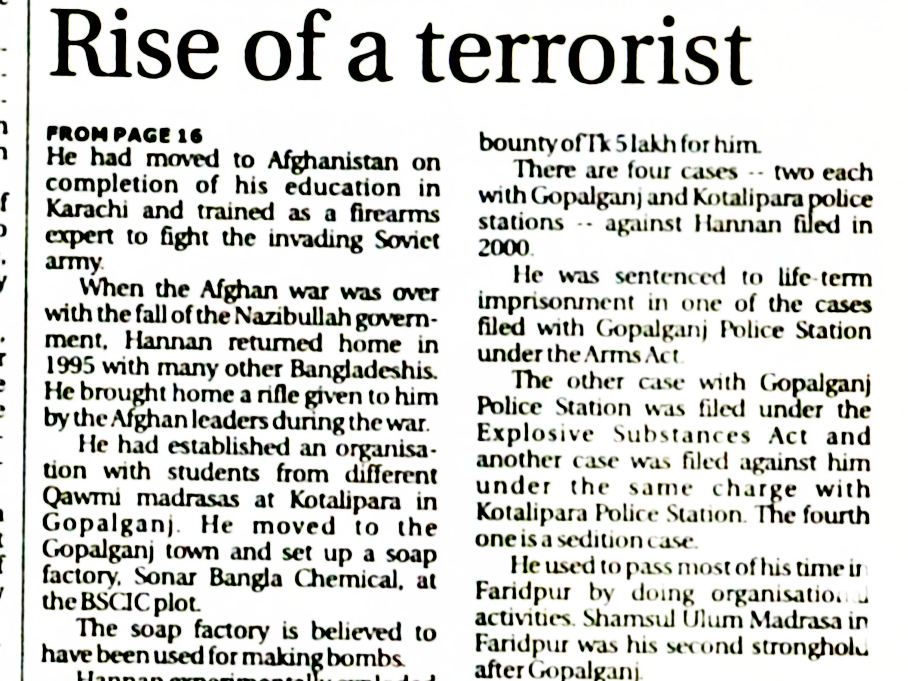

Militancy and Islamist extremism rose during Sheikh Hasina’s rule. More than 80 people were killed in Harkat-ul-Jihad Bangladesh’s (Huji-B) militant attacks in different places, including New Year celebrations and a Catholic Church. Mufti Hannan, in 1999, declared to capture the state power through an armed movement at Pourapark in Gopalganj. Hasina’s government awarded land in state-run BSCIC in Gopalganj to Huji-B leader Mufti Hannan’s brother, which was used as the bomb factory.

These led to Sheikh Hasina’s fall. In October 2001, Khaleda Zia returned as prime minister, as the BNP-led alliance won in more than two-thirds of the constituencies.

Khaleda’s second premiership saw a rise in criminal activities and repression of minority communities. To control the situation, she deployed the Army with magistracy power under ‘Operation Clean Heart’. Many BNP cadres and AL-backed alleged criminals were killed extrajudicially. She also introduced the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), a force that became known as the death squad, for killing countless individuals in staged crossfire.

Militant extremism also grew during Khaleda’s rule. Hundreds died in dozens of bomb attacks, including a gruesome one on her arch-rival Sheikh Hasina in 2004. RAB and Police eventually hunted down the militant’s network after a series of bomb blasts in 2005.

On the education front, cheating at public examinations was stopped. Acid crime also significantly decreased after serious state-led coordinated actions. Militancy was checked as well.

The economy, however, grew by an average of 5% each year despite high corruption, which put Bangladesh at the top of Transparency International’s global ranking on corruption perception. The power sector struggled due to the alleged corruption and wrong policies.

Khaleda Zia’s government tried to tamper with the caretaker government system, which resulted in fierce street protests led by the Awami League. Dozens died, and the military stepped in and staged a coup under civilian cover.

The military-backed caretaker regime was officially under Fakhruddin Ahmed but was unofficially led by Army Chief Moeen U Ahmed. The government tried to impose serious reforms but to no avail. Politicians accused of amassing illegal wealth were arrested left and right. But hardly anything was proven against them.

A student-led protest shook the regime’s foundation in August 2007, and Moeen explored the political options for a smoother transition. Mediated by India’s ruling Congress’s senior leader, Pranab Mukherjee, Moeen agreed to support AL’s return to power. A new election was held in the last week of 2008, and AL won an unprecedented victory while BNP was reduced to only 30 seats in the parliament.

Abusing the brute majority in the parliament, Hasina-led AL became more authoritarian than ever after 2010. The constitution was amended to remove the caretaker government system, making fair elections impossible. BNP came out of the streets demanding the restoration of the caretaker government system, hundreds were killed, and dozens fell victim to enforced disappearances across the country as Hasina’s loyalists in police and security forces enforced a brutal crackdown on opposition activists from 2012 to 2013.

The power sector, struggling under Khaleda Zia’s tenure, performed better under Hasina, and generation capacity grew almost fivefold in 15 years. The economy grew by 6% on average. However, The success was short-lived as the growth was heavily reliant on imported fossil fuels, which created pressure on the economy.

The foreign reserve started falling sharply as demand for imports grew, coupled with the economic slowdown due to COVID. Financial mismanagement and plunders in the banking sector, often supported by the close allies of Sheikh Hasina, complicated the situation.

Sham elections were held in 2014, 2018, and 2024. All major opposition parties boycotted the 2014 and 2024 elections, while the election in 2018 was termed a ‘Midnight Vote’ since ballots were stuffed in the night before.

Prominent global leaders, including hundreds of Nobel laureates and global democracy watchdogs, questioned the elections under Hasina.

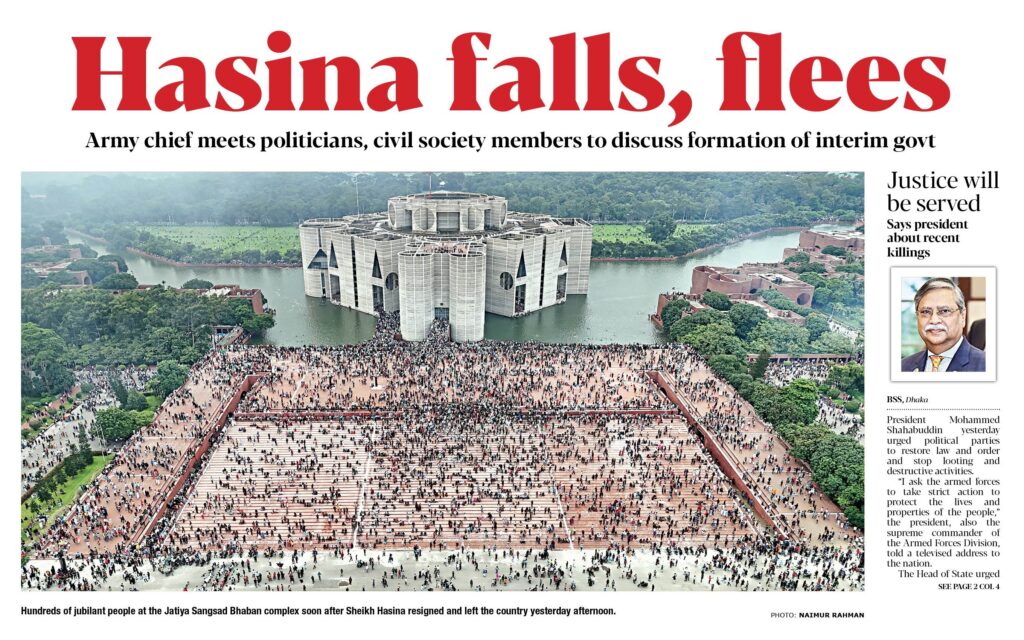

In July 2024, Hasina ordered another crackdown on student protesters who were protesting the restoration of a discriminatory quota-based recruitment system that claimed more than two hundred lives in less than a week. This snowballed into a larger anti-Hasina one-point movement in early August. People from all sections of society and almost all pro-democracy political parties came down on the streets to support the students.

Sheikh Hasina fled on August 5, 2024, after offering her resignation, to India in the face of the mass uprising.

Nobel laureate Dr Muhammad Yunus took charge as the Chief Adviser and formed a new government on August 8, 2024.